|

||

|

HOME

|

US Navy -

ships

|

US Navy - air

units

|

USMC - air

units

|

International

Navies

|

Weapon Systems

|

Special Reports |

||

|

US Navy - Aircraft Carrier CVN 71 - USS Theodore Roosevelt |

||

|

||

| 04/25 | ||

|

Type, class:

Aircraft Carrier - CVN; Nimitz class Builder: Newport News Shipbuilding, Newport News, Virginia, USA STATUS: Awarded: September 30, 1980 Laid down: October 31, 1981 Launched: October 27, 1984 Commissioned: October 25, 1986 IN SERVICE Homeport: NAS North Island, San Diego, California Namesake: Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), 26th President of the USA Ships Motto: QUI PLANTAVIT CURABIT (he who has planted will preserve) Technical Data: see: INFO > Nimitz class Aircraft Carrier - CVN |

||

|

Deployments / Carrier Air Wings embarked / major maintenance periods: January 1987 - February 1987 with Carrier Air Wing 1 (CVW-1) - shakedown cruise - Caribbean Sea March 1987 - July 1987: Post Shakedown Availability at Newport News Shipbuilding, Virginia August 1988 - October 1988 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Atlantic Ocean December 1988 - June 1989 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea July 1989 - November 1989: Selected Restricted Availability (SRA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia December 1990 - June 1991 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Operation Desert Shield + Desert Storm October 1991 - May 1992: Drydocking Selected Restricted Availability (DSRA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia March 1993 - September 1993 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea November 1993 - April 1994: Selected Restricted Availability (SRA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia March 1995 - September 1995 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea November 1995 - March 1996: Selected Restricted Availability (SRA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia November 1996 - May 1997 with Carrier Air Wing 3 (CVW-3) - Mediterranean Sea July 1997 - July 1998: Extended Selected Restricted Availability (EDSRA) at Newport News Shipbuilding, Virginia March 1999 - September 1999 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea, Gulf January 2000 - June 2000: Planned Incremental Availability (PIA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia September 2001 - March 2002 with Carrier Air Wing 1 (CVW-1) - Mediterranean Sea, Arabian Sea May 2002 - October 2002: Planned Incremental Availability (PIA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia February 2003 - May 2003 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea February 2004 - December 2004: Planned Incremental Availability (PIA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia September 2005 - March 2006 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea, Gulf March 2007 - November 2007: Planned Incremental Availability (PIA) at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Virginia September 2008 - April 2009 with Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) - Mediterranean Sea, 5th Fleet AOR August 2009 - August 2013: Refueling and Complex Overhaul (RCOH) at Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock, Virginia March 2015 - November 2015 with Carrier Air Wing 1 (CVW-1) - Norfolk to San Diego via 6th, 5th and 7th Fleet AOR May 2016 - December 2016: Planned Incremental Availability (PIA) at Naval Base San Diego, California October 2017 - May 2018 with Carrier Air Wing 17 (CVW-17) - Pacific Ocean, Gulf July 2018 - December 2018: Planned Incremental Availability (PIA) at Naval Base San Diego, California May 2019 with Carrier Air Wing 11 (CVW-11) - Gulf of Alaska - exercise Northern Edge January 2020 - July 2020 with Carrier Air Wing 11 (CVW-11) - Pacific Ocean December 2020 - May 2021 with Carrier Air Wing 11 (CVW-11) - Pacific Ocean July 2021 - March 2023: Drydocking Selected Restricted Availability (DSRA) at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Washington January 2024 - ?? with Carrier Air Wing 11 (CVW-11) - Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean |

||

| images | ||

with CVW-11 embarked - Naval Base Guam, Apra Harbor - September 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - 5th Fleet AOO - August 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - June 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - June 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Changi Naval Base, Singapore - May 23, 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - Laem Chabang, Thailand - April 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - 7th Fleet AOR - April 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - January 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - January 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - January 2024  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - September 2023  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - September 2023  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - September 2023  returning to her homeport NAS North Island, San Diego, California after a 28-month DPIA at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard - March 2023  returning to her homeport NAS North Island, San Diego, California after a 28-month DPIA at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard - March 2023  departing Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington after her scheduled DPIA - March 2023 July 2021 - March 2023: Drydocking Planned Incremental Availability (DPIA) at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington  arriving at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington for her scheduled DPIA - July 2021  arriving at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington for her scheduled DPIA - July 2021  returning to Naval Base San Diego, California - May 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Gulf of Alaska - May 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - April 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - April 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - April 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Indian Ocean - March 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Indian Ocean - March 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Indian Ocean - March 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Indian Ocean - March 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Indian Ocean - March 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Indian Ocean - March 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - February 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - February 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - February 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2021  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - December 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - departing Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - June 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - May 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - May 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - May 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - May 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - May 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Apra Harbor, Guam - May 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Philippine Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - South China Sea - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Da Nang, Vietnam - March 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - February 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - February 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - arriving at Apra Harbor, Guam - February 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - January 2020  departing San Diego, California - January 17, 2020  departing San Diego, California - January 17, 2020  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - November 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - Pacific Ocean - July 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-11 embarked - exercise Northern Edge - Gulf of Alaska - May 2019  with CVW-17 embarked - Pacific Ocean - May 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pacific Ocean - May 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pacific Ocean - May 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pearl Harbor, Hawaii - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pearl Harbor, Hawaii - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pearl Harbor, Hawaii - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pearl Harbor, Hawaii - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pacific Ocean - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Pacific Ocean - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - South China Sea - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Changi Naval Base, Singapore - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Changi Naval Base, Singapore - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Changi Naval Base, Singapore - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Strait of Malacca - April 2018 (celebrating the 125th birthday of the Navy chief petty officer / CPO rate)  with CVW-17 embarked - Strait of Malacca - April 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Arabian Gulf - March 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Arabian Gulf - March 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Arabian Gulf - February 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Arabian Gulf - February 2018  with CVW-17 embarked - Arabian Gulf - January 2018 > continue - CVN 71 image page 2 < |

||

Theodore Roosevelt

|

||

|

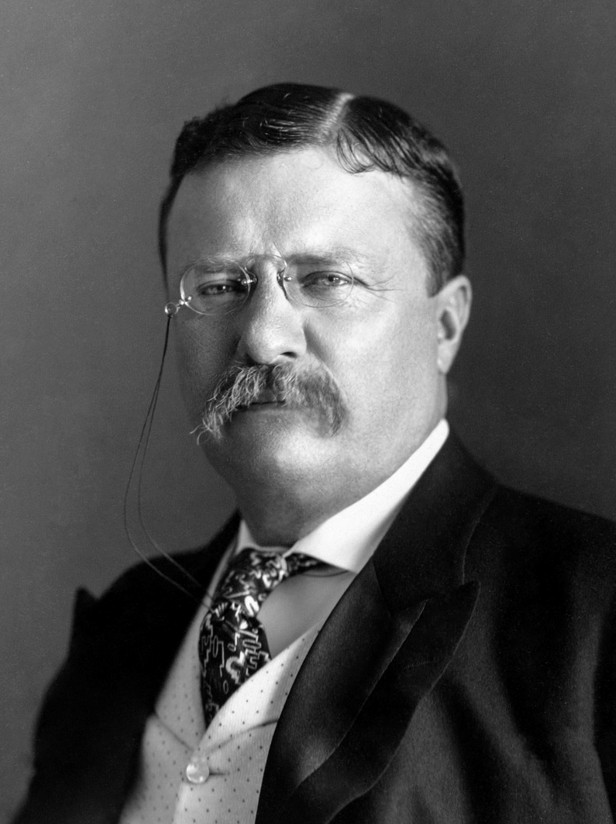

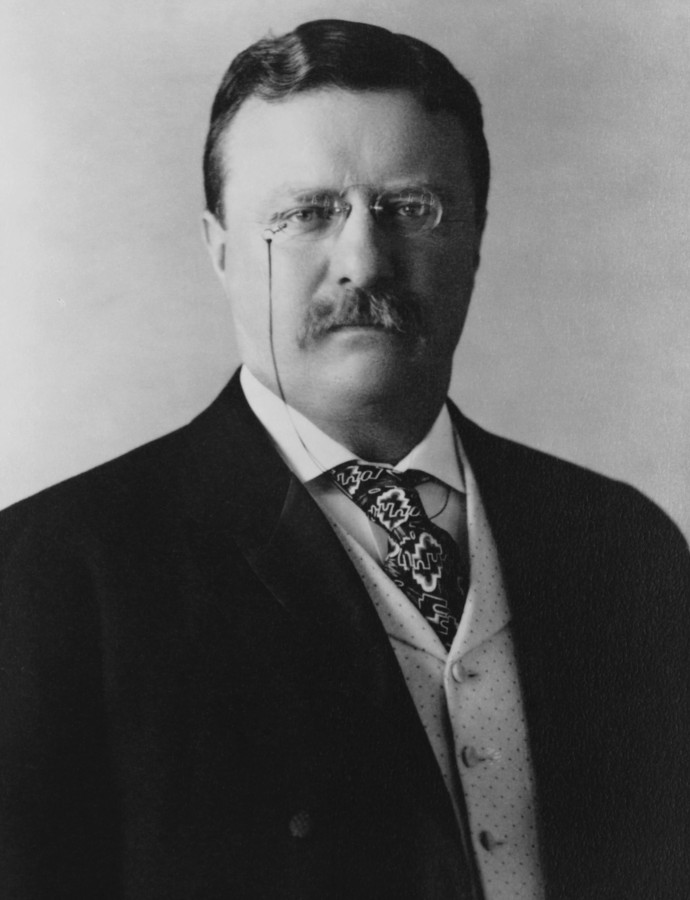

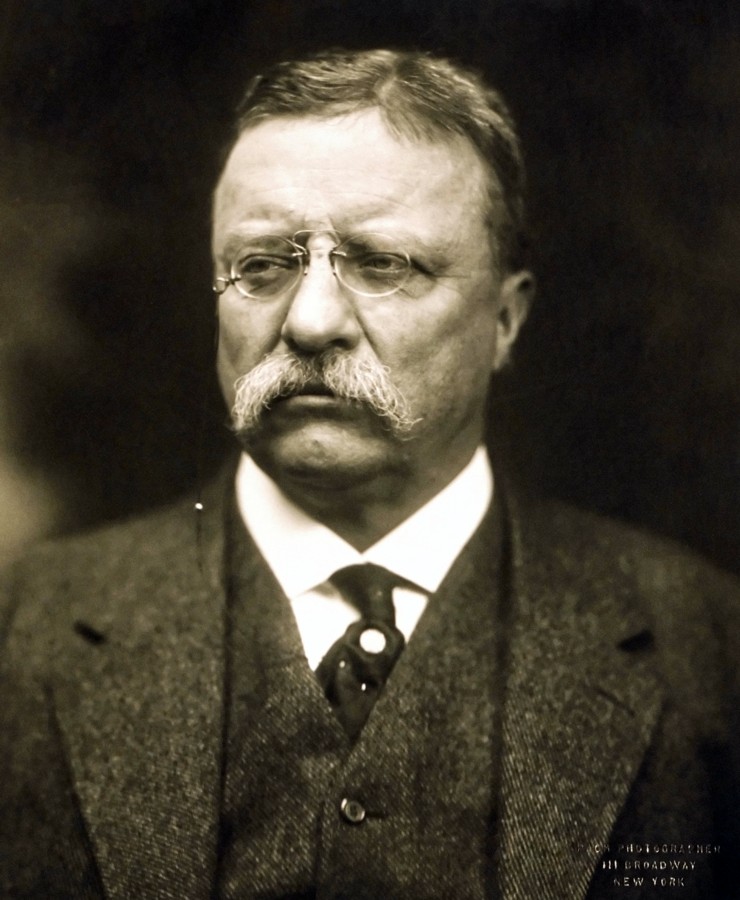

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October

27, 1858 - January 6, 1919): ... was an American statesman, author, explorer, soldier, naturalist, and reformer who served as the 26th President of the United States from 1901 to 1909. As a leader of the Republican Party during this time, he became a driving force for the Progressive Era in the United States in the early 20th century. Born a sickly child with debilitating asthma, Roosevelt successfully overcame his health problems by embracing a strenuous lifestyle. He integrated his exuberant personality, vast range of interests, and world-famous achievements into a "cowboy" persona defined by robust masculinity. Home-schooled, he began a lifelong naturalist avocation before attending Harvard College. His first of many books, The Naval War of 1812 (1882), established his reputation as both a learned historian and as a popular writer. Upon entering politics, he became the leader of the reform faction of Republicans in New York's state legislature. Following the deaths of his wife and mother, he took time to grieve by escaping to the wilderness of the American West and operating a cattle ranch in the Dakotas for a time, before returning East to run unsuccessfully for Mayor of New York City in 1886. He served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under William McKinley, resigning after one year to serve with the Rough Riders, where he gained national fame for courage during the Spanish–American War. Returning a war hero, he was elected governor of New York in 1898. The state party leadership distrusted him, so they took the lead in moving him to the prestigious but powerless role of vice president as McKinley's running mate in the election of 1900. Roosevelt campaigned vigorously across the country, helping McKinley's re-election in a landslide victory based on a platform of peace, prosperity, and conservatism. Following the assassination of President McKinley in September 1901, Roosevelt, at age 42, succeeded to the office, becoming the youngest United States President in history. Leading his party and country into the Progressive Era, he championed his "Square Deal" domestic policies, promising the average citizen fairness, breaking of trusts, regulation of railroads, and pure food and drugs. Making conservation a top priority, he established a myriad of new national parks, forests, and monuments intended to preserve the nation's natural resources. In foreign policy, he focused on Central America, where he began construction of the Panama Canal. He greatly expanded the United States Navy, and sent the Great White Fleet on a world tour to project the United States' naval power around the globe. His successful efforts to end the Russo-Japanese War won him the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. Elected in 1904 to a full term, Roosevelt continued to promote progressive policies, but many of his efforts and much of his legislative agenda were eventually blocked in Congress. Roosevelt successfully groomed his close friend, William Howard Taft, to succeed him in the presidency. After leaving office, Roosevelt went on safari in Africa and toured Europe. Returning to the USA, he became frustrated with Taft's approach as his successor. He tried but failed to win the presidential nomination in 1912. Roosevelt founded his own party, the Progressive, so-called "Bull Moose" Party, and called for wide-ranging progressive reforms. The split among Republicans enabled the Democrats to win both the White House and a majority in the Congress in 1912. The Democrats in the South had also gained power by having disenfranchised most blacks (and Republicans) from the political system from 1890 to 1908, fatally weakening the Republican Party across the region, and creating a Solid South dominated by their party alone. Republicans aligned with Taft nationally would control the Republican Party for decades. Frustrated at home, Roosevelt led a two-year expedition in the Amazon Basin, nearly dying of tropical disease. During World War I, he opposed President Woodrow Wilson for keeping the U.S. out of the war against Germany, and offered his military services, which were never summoned. Although planning to run again for president in 1920, Roosevelt suffered deteriorating health and died in early 1919. Roosevelt has consistently been ranked by scholars as one of the greatest U.S. presidents. His face was carved into Mount Rushmore alongside those of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln. |

||

|