|

||

|

HOME

|

US Navy -

ships

|

US Navy - air

units

|

USMC - air

units

|

International

Navies

|

Weapon Systems

|

Special Reports |

||

|

US Navy - Guided Missile Destroyer DDG 72 - USS Mahan |

||

|

||

| 06/25 | ||

|

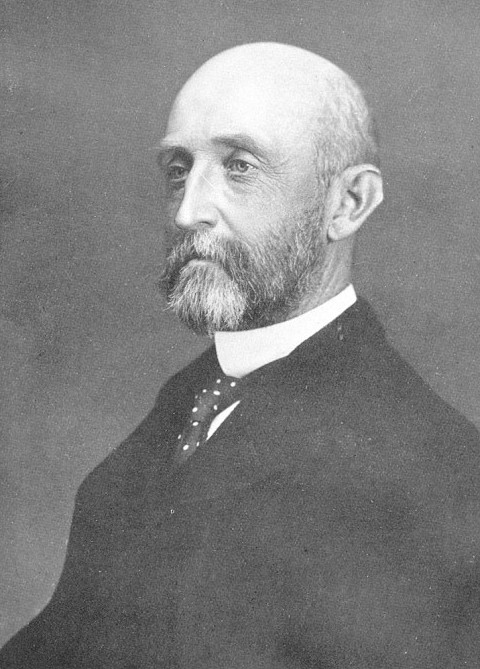

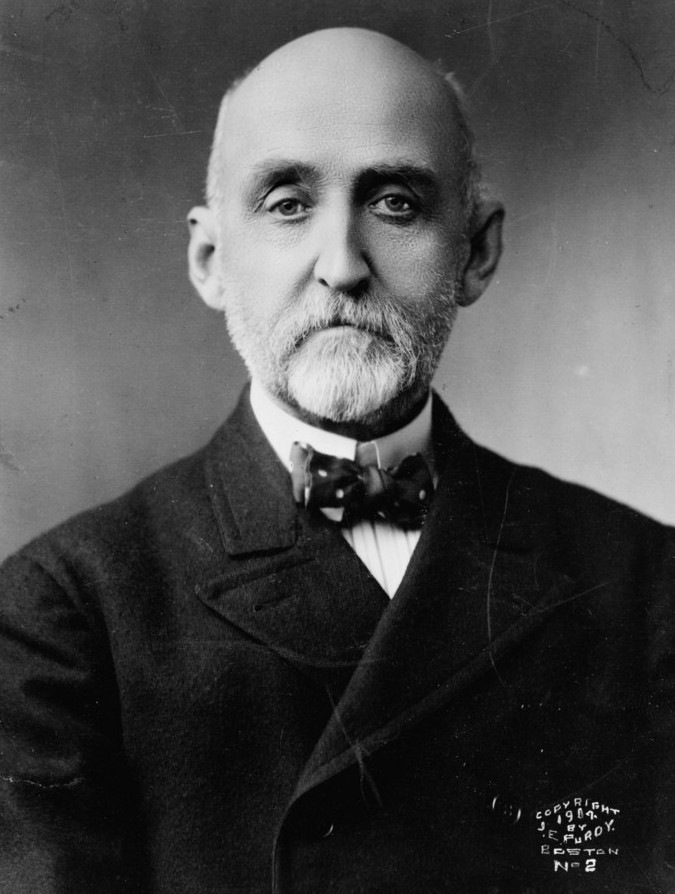

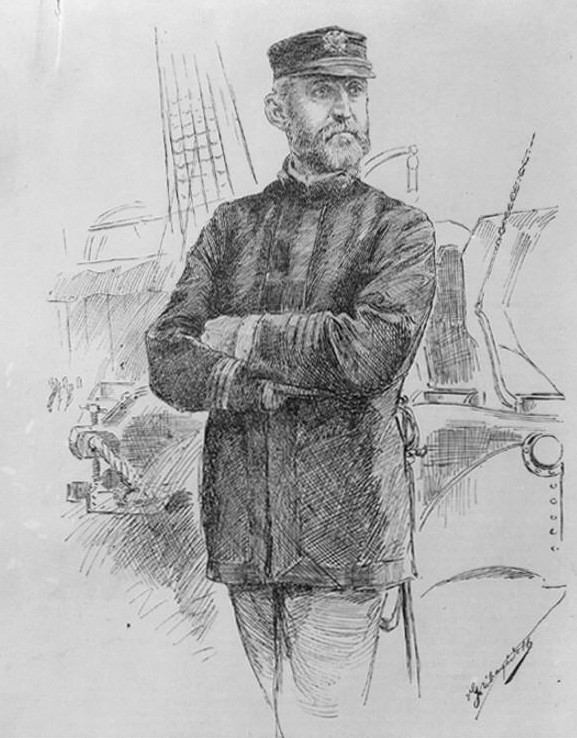

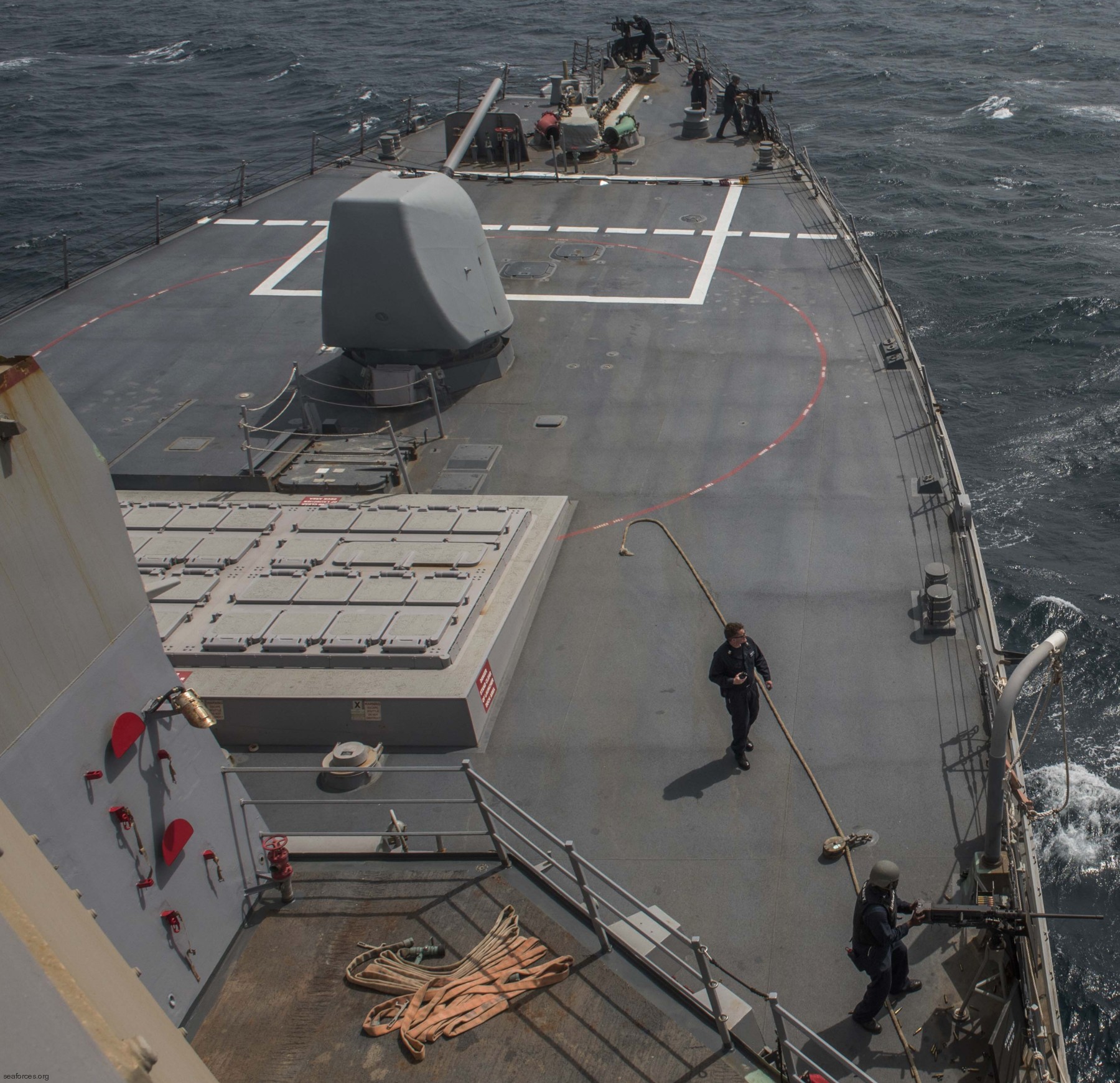

Type,

class: Guided Missile Destroyer - DDG; Arleigh Burke

class, Flight II Builder: Bath Iron Works, Bath, Maine, USA STATUS: Awarded: April 8, 1992 Laid down: August 17, 1995 Launched: June 29, 1996 Commissioned: February 14, 1998 IN SERVICE Homeport: Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia Namesake: Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) Ships Motto: BUILT TO FIGHT Technical Data: see: INFO > Arleigh Burke class Guided Missile Destroyer - DDG see also > USS Mahan (DDG 42) see also > Special Report / USS Mahan (DDG 72) in Trieste / Italy |

||

| images | ||

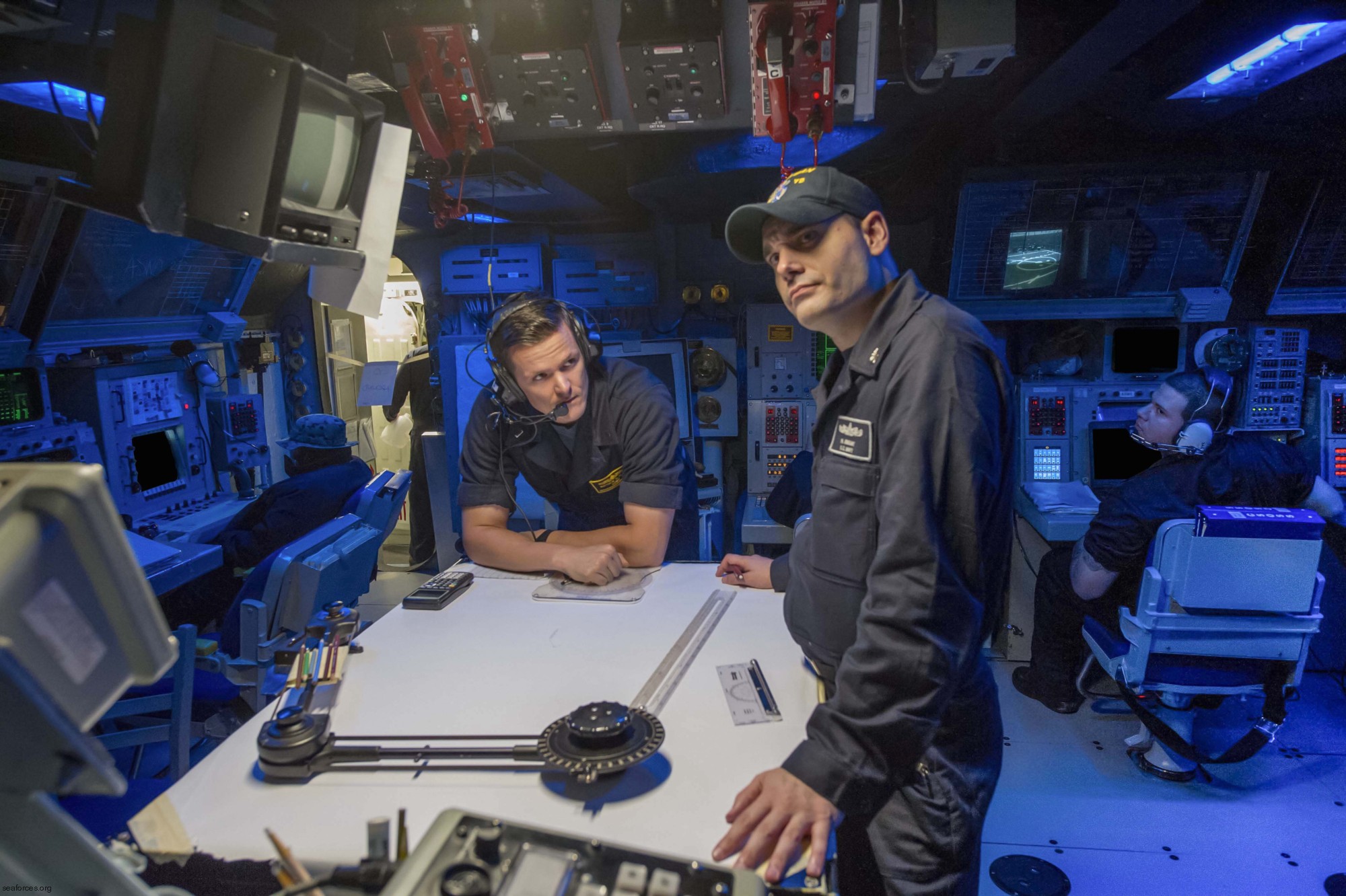

departing Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - June 24, 2025  Atlantic Ocean - April 2025  Atlantic Ocean - April 2025 2022-2023: 22-month Selected Restricted Availability (SRA) at Marine Hydraulics Industries (MHI) Ship Repair & Services Shipyard, Norfolk  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - August 6, 2021  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - August 6, 2021  Naval Support Activity Souda Bay, Crete, Greece - March 2021  Atlantic Ocean - February 2021  Atlantic Ocean - January 2021  Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - September 2019  Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - September 2019  Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - September 2019  Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - September 2019  Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - September 2019  Mk.38 Mod.1 machine gun fire - Arabian Sea - March 2017  Mk.45 Mod.2 gun fire - Arabian Sea - January 2017  departing Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - November 19, 2016  Atlantic Ocean - September 2016  firing a Standard Missile during an exercise - Atlantic Ocean - September 2016  combat information center (CIC) - July 2016  Atlantic Ocean - July 2016  Atlantic Ocean - July 2016  Atlantic Ocean - July 2016  Atlantic Ocean - July 2016  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - January 10, 2015  off Bahrain - September 2014  off Bahrain - September 2014  off Bahrain - September 2014  Mk.32 torpedo tubes exercise - Manama, Bahrain - September 2014  fuel control console - August 2014  departing Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - August 2014  Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - December 2013  Mk.45 gun fire exercise - Atlantic Ocean - November 2013  Mediterranean Sea - August 2013  Naval Support Activity Souda Bay, Crete, Greece - May 2013  Mediterranean Sea - April 2013  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - June 2011  departing Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - November 2010  Mk.45 gun fire exercise - Atlantic Ocean - June 2010  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - April 9, 2009  Indian Ocean - October 2008  Atlantic Ocean - July 2008  Atlantic Ocean - July 2008  Atlantic Ocean - July 2008  Baltic Sea - May 2007  Baltic Sea - May 2007  bridge - Baltic Sea - May 2007  Mindelo, Cape Verde - April 2007  Curacao, Netherlands Antilles - April 2007  Boston, Massachusetts - February 2007  Boston, Massachusetts - February 2007  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - November 2005  returning to Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - November 2005  departing Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia - May 2005  September 2002  builder's trials - July 1997  builder's trials - July 1997  builder's trials - July 1997  builder's trials - July 1997  builder's trials - July 1997  builder's trials - July 1997  christening & launching ceremony at Bath Iron Works, Maine - June 29, 1996 |

||

|

USS Mahan (DDG 72): The keel of Mahan was laid on 17 August 1995. Her mast was stepped on 6 February 1996, and she was launched and christened later that year on 29 June. The ship's sponsor is Mrs. Jennie Lou Arthur, wife of Admiral Stan Arthur. Her Aegis Combat System was lit off on 19 December. 1997 was a busy year for Mahan. Alpha/Bravo trials occurred on 21 July, Charlie trials on 5 August, and Delta trials on 12 August. The ship was officially transferred to the Navy on 22 August, and her Crew moved aboard on 17 October. The ship’s first underway was 16-17 January 1998 from Bath, Maine, to Portland, Maine, for a three-day port visit. The weather was particularly heavy, and many of the crew members who had not put to sea before felt the effects of seasickness. Underway from Portland on 21 January, the ship pulled into her new homeport of Norfolk, Virginia, on 24 January. Mahan stayed in Norfolk until departing for her commissioning ceremony. Mahan was commissioned at 1100 on 14 February 1998 at Tampa, Florida by the Commander, Naval Surface Forces Atlantic, Vice Admiral Henry C. Griffin, III, USN with Commander Michael L. James, USN, commanding. Distinguished guests included Mr. Allen Cameron, President of Bath Iron Works, the Hon. Charles T. Canady, Congressman from Florida’s 12th District, and the Hon. George Nethercutt, Congressman from Washington’s 5th District. Mahan stayed in Tampa until 17 February, returning to Norfolk on 21 February. Mahan briefly left at the end of the month to conduct Combat Direction Finding System testing at sea. The next few months saw events including Command Assessment of Readiness and Training (CART), ammunition onload at Yorktown Naval Weapons Station, Tailored Ship’s Training Availability (TSTA), Industrial Hygiene Survey, Combat Systems Ship’s Qualification Trial (CSSQT), evaluation at the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC), MISSILEX, Naval Surface Fire Support (NSFS) qualification, VANDALEX, Final Conduct Trial, a post-Shipyard Availability Conference, and a recruiting video shoot, all before the end of July. In August, Mahan hosted the change of command ceremony for Commander Destroyer Squadron 26. Mahan was placed in drydock in Portland, Maine on 1 September as part of the post-Shipyard Availability (PSA). Mahan departed Portland on 16 November, and during the transit back to Norfolk, conducted her first underway replenishment, with USNS Big Horn. The ship was underway twice for Helicopter Deck Landing Qualifications (DLQs) before the end of the year. On 16 February 2007, Mahan was awarded the 2006 Battle "E" award. In June 2009, Mahan participated as an opposition force unit during USS Harry S. Truman's Composite Training Unit Exercise (COMPTUEX). In July 2009, Mahan participated in Operation Northern Trident, where she met two Royal Australian Navy ships, HMAS Sydney and HMAS Ballarat, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The three ships conducted combined exercises at sea and a four-day port visit to New York City, New York. Mahan crew members worked with their Australian counterparts in cleaning the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines Center in midtown Manhattan. Receptions were held onboard all three ships while offering tours to the public. Crew members were able to pay their respects by conducting a wreath laying ceremony at the World Trade Center. Several sailors also reenlisted in Times Square and at the World Trade Center site. USS Mahan began a Selected Restricted Availability (SRA) at the BAE Systems Ship Repair shipyard in Norfolk, Virginia on 6 January 2010. The extensive upgrades and installations received during this time focused on improving the ship's Command and Control capability. Mahan left the shipyard on 10 March, and completed a light-off assessment on 25 March, ending the SRA. The remainder of 2010 was dedicated to completing Basic Phase training, which had commenced prior to starting the SRA in 2009, conducting Integrated Phase training, and final repairs and installations to ensure Mahan was materially ready for an extended deployment. Mahan participated in the USS Kearsarge Amphibious Readiness Group's COMPTUEX in July, resulting in certification for maritime support operations. Mahan's executive officer was relieved on 17 September 2010 following an investigation and commodore's mast. In August 2011, USS Mahan made a port visit to Rockland, Maine, in support of the 64th annual Maine Lobster Festival. The crew participated in a parade, tours, a cooking contest, community service projects, and a 10K race. Later that month, Mahan visited Newport, Rhode Island to be the Surface Warfare Officer's School (SWOS) Ship for the week of 15-19 August. Mahan was sortied along with 26 other ships in preparation for Hurricane Irene, returning 1 September 2011. Mahan began a Selected Restricted Availability (SRA) at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries shipyard in Norfolk, Virginia on 26 October 2011. During this availability, the ship received the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System upgrade. Commander Adam Aycock relieved Commander Kurt Mondlak as commanding officer on 4 November 2011. USS Mahan held a memorial ceremony on 6 December 2013, in honor of the 69th anniversary of the Battle of Ormoc Bay in which USS Mahan (DD 364) lost six crewmembers. On 10 January 2014, three USS Mahan (DDG 72) sailors traveled to Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, to present a flag to a veteran of USS Mahan (DD 364) who was unable to make the December ceremony. USS Mahan visited New Orleans, Louisiana, during the 2014 Mardi Gras celebration. A shooting occurred on the ship just before midnight on 24 March 2014, while the ship was pier-side at Naval Station Norfolk in Norfolk, Virginia. Master-At-Arms Second Class Mark Mayo who was on duty as the Chief of the Guard, dove in front of the ship's Petty Officer of the Watch to shield her from the gunman. For his actions, he was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. A Navy sailor was killed and the civilian suspect was shot and killed by Naval Security Forces. The civilian armed himself by wrestling the weapon free from a Norfolk Naval Station Guard. USS Mahan's SRA ended on 29 February 2012, which was immediately followed by a light-off assessment and sea trials. The ship went through four Continuous Maintenance Availabilities (CMAVs) in April, June, September, and November. Following a command investigation, 13 Mahan sailors were awarded non-judicial punishment for illegal drug use during a captain's mast on 4 April 2012. On 10 April 2012, Mahan hosted a retired Chief Sonar Technician. In June and July, Mahan hosted midshipmen from the United States Naval Academy and Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps as part of Cortramid. In October, Mahan was evaluated by the Board of Inspection and Survey as part of a regularly scheduled inspection. Not only was Mahan the first ship to successfully demonstrate Ballistic Missile Defense during the inspection, the ship also achieved the highest score for a destroyer in several years. Later in October, Mahan was the host ship for the United States Naval Academy Homecoming Weekend in Annapolis, Maryland. The ship completed Independent Deployer Certification Exercise (IDCERTEX) in December in preparation for her upcoming deployment. Deployments: March 2000 - August 2000 Mediterranean Mahan departed Norfolk, Virginia, on 19 February 2000, on her maiden deployment to the Meditrranean as part of the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower Battle Group. She returned home on 18 August later that year. June 2002 - December 2002 North Atlantic-Med-Indian Ocean Mahan's second deployment began when she departed Norfolk, Virginia, 20 June 2002. While deployed to the Mediterranean and North Atlantic Ocean, she made port visits in France, Scotland, Spain, Gibraltar, Slovenia, Crete, Malta, and the United Kingdom. She returned 20 December the same year. October 2006 - November 2006 Exercise NEPTUNE WARRIOR January 2007 - July 2007 Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 (SNMG-1) September 2008 - April 2009 North Atlantic-Med-Indian Ocean November 2010 - June 2011 North Atlantic-Med-Indian Ocean Mahan left Naval Station Norfolk on 7 November 2010, for a maritime security operation deployment as part of United States Naval Forces Europe to the Horn of Africa. The ship made port visits in Haifa, Israel, Djibouti, Djibouti, Souda Bay, Crete, and Istanbul, Turkey. The ship also stopped for fuel in Naval Station Rota in Spain. Mahan transited through the Suez Canal, the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, the Dardanelles, and the Strait of Gibraltar. The ship returned to Naval Station Norfolk on 8 June 2011. During the 2011 maritime security operation deployment, USS Mahan was dispatched to the Mediterranean Sea to conduct operations in Libya. Insitu Inc. announced that its ScanEagle been assisting U.S. and NATO Forces in their mission to protect civilians and reduce the flow of arms to Libya. During a 72-hour counter-terrorism surge supporting Operation Unified Protector, the ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicle was operated organically aboard Mahan to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance support. In strong winds, ScanEagle performed cooperatively with a host of US and NATO participating forces. On this deployment ScanEagles (the second aboard Mahan) the team achieved a 100 percent mission readiness rate, accruing 1,154 flight hours and 167 sorties. 28 December 2012 - 13 September 2013 USS Mahan left Naval Station Norfolk on 28 December 2012, for a maritime security operation deployment to the United States Sixth Fleet Area of Responsibility. The ship made port visits in Augusta Bay, Sicily, Naples, Italy, Haifa, Israel, Limassol, Cyprus, Souda Bay, Crete, Rhodes, Greece, and Larnaca, Cyprus. The crew participated in community relations projects at every port. The ship also stopped for fuel in Funchal, Madeira and Naval Station Rota in Spain. During Mahan's visit to Rhodes, Commander Zoah Scheneman relieved Commander Adam Aycock as commanding officer on 7 May 2013. Mahan remained in theater after the Ghouta chemical attack in Syria. Mahan returned on 13 September 2013, and had a pinning ceremony for ten (10) chief petty officer selects as soon as the ship was moored. On 9 January 2017, Sky News reported that whilst escorting two other US ships, the USS Mahan fired three warning shots at four Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard boats in the Strait of Hormuz after the Iranians did not respond to requests by the Mahan to slow down and instead continued asking the ship questions, coming to within 800m of the Mahan. According to the officials speaking anonymously to Reuters, a helicopter dropped a smoke float and the destroyer launched flares but the boats continued at speed. A similar incident occurred on 24 April 2017. source: wikipedia |

||

|

Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (September 27, 1840 -

December 1, 1914): Alfred Thayer Mahan was born on 27 September 1840 at West Point, New York, where his father, Dennis Hart Mahan, was a distinguished professor of Civil and Military Engineering at the US Military Academy. He died in Washington, DC on 1 December 1914, and is buried at Quogue, Long Island. Young Mahan spent his early years at West Point, until he was sent to a boarding school in Maryland, St. James School, near Hagerstown, in 1852. Two years later he entered Columbia College, in New York City, and through the influence of Jefferson Davis, he obtained an appointment to the Naval Academy, and by special arrangement (the only occasion on record of that concession being made) he entered the Third Class, on 7 October 1856, as Acting Midshipman. He was graduated from the Naval Academy in 1859, second in his class of twenty members, rose to the rank of Lieutenant during the Civil War, became a Captain in 1885, and was transferred to the Retired List of the Navy, at his own request, on 17 November 1896. He was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral on the Retired List, with date of rank 29 June 1906. After his graduation from the Naval Academy in 1859, he was assigned to the frigate Congress from 9 June 1859 until 1861. He then joined the steam-corvette Pocahontas of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, and participated in the attack on Port Royal, South Carolina, early in the Civil War. During that cruise, from which he was detached in 1862, he wrote a letter to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy suggesting that a sailing ship be outfitted as a "mystery" ship to decoy Confederate blockade runners. He was next sent to the Naval Academy, then at Newport, Rhode Island, as an instructor, and during the summer of 1863 he made a cruise with the midshipmen to Europe in the Macedonian. In October 1863 he joined the Seminole of the West Coast Blockading Squadron and later served on the staff of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, USN, Commander, South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, off Charleston, South Carolina. He reported on 31 May 1865 to the Mucoota, and soon thereafter was transferred to the Iroquios, in which he went to the Orient. He was present at the opening of the treaty ports of Kobe and Osaka, Japan in 1867. Completing his duty on China Station in 1869, he was granted permission to visit in Europe, and after his return to the United States was ordered to the USS Worcester, chartered by the Navy Department as a relief ship to carry foodstuffs to the French people who had been reported in dire need. He was detached from that duty on 3 August 1871 and in December 1872 assumed his first command, the USS Wasp, of the South Atlantic Squadron. He continued in that command until January 1875, when he was ordered to return to the United States, and home to await further orders. In August 1876, he was designated as a member of the Board of Examiners at the Naval Academy, and during his period of duty there he won third prize in 1878 in the Naval Institute's contest for the best essay on "Naval Education for Officers and Men." This was the first article he had accepted for publication. In the summer of 1880 he was ordered to the Navigation Department, New York Navy Yard, and on 9 September 1883, he assumed command of the Wachusett at Callao, Peru. In the Wachusett he visited ports on the west coast of South America. In October 1885 he was assigned duty as Lecturer on Naval Tactics and History at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, and in 1886 he was appointed President of the Naval War College. He had additional duty, while there, as President of the Commission to select the site for a Navy Yard on the Pacific Coast, in the region of Puget Sound, and for a short period was attached to the Bureau of Navigation, Navy Department, Washington, DC. In 1890 he wrote Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783, the first of twenty books and twenty-three essays on this broad subject. In 1893 he was given command of the USS Chicago, flagship of a squadron sent to European waters to return visits made by foreign vessels during the celebration in 1892-1983 of Columbus' discovery of America. After a cruise of Northern Europe and Mediterranean ports, the Chicago under Captain Mahan's command, returned to the United States in March 1895, and in May he returned to the Naval War College for special duty. At his own request he was retired on 17 November 1896, after forty years of active service, in order to devote his full time to writing on naval subjects. He returned to active duty at the beginning of the Spanish-American War, and in May 1898 was appointed to the Naval Board of Strategy. In 1899 he served as one of the American delegates at the First Peace Conference at the Hague, The Netherlands. During the years to follow, he was recalled to active service as Member of the Board of Visitors, Naval Academy, (May 1903); with the Senate Commission on Merchant Marine (November 1904); to report on studies and conclusions of the Naval War Board during the War with Spain (July 1906); as a Member of the Committee on Documentary Historical Publications under the Committee on Departmental Methods (October 1908); as a Member of the Commission to Report on Re-organization of the Navy Department (February 1909); and to lecture at the Naval War College. During the period 1884 until his death in 1914, Admiral Mahan studied and wrote on Naval historical and biographical subjects. His works have had tremendous influence all over the world, especially those directly concerning seapower, and have been translated into many different languages. While abroad as Commanding Officer of the USS Chicago in 1894, he was awarded honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge Universities. Later Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Dartmouth and McGill similarly honored him. The Royal United Service Institute awarded him its Chesney Gold Medal in recognition of his literary work bearing on the welfare of the British Empire, in 1900; and in 1902 he was made President of the American Historical Society. source: US Naval History & Heritage Command (NHHC)

|

||

| patches + more | ||

|

||

|

|

seaforces.org

|

USN ships

start page | |